The weeding problem

A discussion of robotic weeding issues

Background

Physicists know that nature is lazy. The crops which will give the most beneficial return for the farmer are probably not the plants best adapted to survive the environment, and are unlikely to consistently win the never-ending competition over space, nutrients, water and sunlight with the other plants around it. The weeds will win.

But naturalists know that all plants want to survive, and all that is needed are mechanisms to give sufficient advantage to to desired plants to enable to take the advantage over the weeds (and hopefully over their parasites too). Farming is not about completely eradicating all weeds and parasites, but simply to disrupt them enough for the crops to get the advantage over the weeds, and using their natural defences against parasites.

Successful farming is not about conquering nature, but tweaking nature's parameters for a result.

General or Specific

Weed control mechanisms fit into two categories - general and specific.

General: apply a process to the whole of the crop which harms weeds more than the crop.

Specific: apply a disruptive mechanism specifically to plants identified as weeds, hence harming the weeds more that the crop.

(The labels are confusing and often used in the reverse sense - a specific herbicide is applied generally to the crop in the hope that it will damage the weeds more than the crop).

A special note about specific and general herbicides is appropriate here.

By example:

- Roundup (aka Glyphosate) is a general herbicide - it kills almost anything it is sprayed on (though some plants may be more resistant than others). Hence it can be sprayed specifically the plants that the operator wants killed.

- Weed-and-feed herbicides (2,4-D, Mecoprop and Dicamba) are specific herbicides, which affect broad-leaf plants more than normal lawn grass. They are sprayed over the whole lawn with expectation that it will damage the broad-leaf plants (weeds) more than the grass. The mechanism is not perfect - it still damages the grass, just not as much as the broad-leaf. The fertiliser (the 'feed' part of weed-and-feed) is added to help the grass recover from the damage done.

General application

Normally farmers use massive booms for general spraying of pesticides (and fertilisers). Humans are expensive and large tractors, while extremely expensive, are actually cost effective if labour costs are high. However, automation can work on a much smaller scale.

This is a small spraying rig designed to be towed behind a small garden tractor. It can spray pesticide (or liquid fertiliser such as Seasol) over a large area, albeit slowly.

Spreading liquid evenly over a large area is actually quite a tricky thing to do - it involves careful flow-rate calculations and, to do the job properly, probably several passes over the same area to even the distribution, and sometimes even carefully marking of areas already covered.

Incorrect application amounts are about more than just wastage. Some pesticides are very harmful to crops or livestock in larger quantities, and also risk polluting the environment.

A spray trailer could be attached the rover, and it could be used to spray the house paddock, or the other paddocks. This would have several possible benefits.

A human doesn't need to breathe in the chemical being sprayed (though there is still the issue with residual chemical being left in soil, plants, food, and the environment).

The chemical could be applied more consistently - as the rover path and rate of spray can be adjusted by more accurate means that human estimation and memory.

This is a small spreader rig designed to be towed behind a small garden tractor. It spreads fertiliser or coarse seeds over a large area.

Solids too are hard to spread evenly.

Normally both of these would be considered to too small for a farm because of the excessive time required sitting on a tractor - the most expensive thing to buy is human labour. However they are ideal applications for an autonomous rover. The rover can simply tow the applicators over a pre-determined course - as fast, as slow, and as often as required.

In the case of the spreader, the rate of use is determined by the rate of wheel turn (and the manual rate lever, which could be replaced by an actuator In the case of the spray rig, the flow rate can be adjusted for speed (as determined by a GPS) by control of the electric pump.

Specific control

While agricultural robotics can be useful in either general or specific weeding applications, the most promise is in specific control mechanisms. An autonomous tractor roving the field spraying chemical over all the crop may be a way to produce a crop more cost effectively (saving the wages of the tractor operator), but it is unlikely to result in less chemical (or less environmentally damaging chemicals) being used. Specific control mechanisms on the other hand promise reduced chemical use.

Employing a small army of farm workers to remove weeds with a hoes is prohibitively expensive for most of the developed world's farms. Employing a small army of robots to remove weeds with a hoe like disruptor is quite plausible

Even employing a small army of farm workers to specifically spray weeds with a the smallest amount of chemical to kill that weed is prohibitively expensive for most of the world's farms. Employing a small army of robots to spray small amounts of herbicide into plants identified as weeds is quite plausible

Specific control is about stressing a weed, and making sure it is more stressed than the crop plants around it. Stressing might be done by

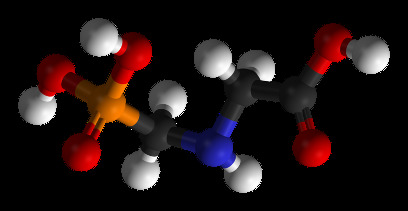

- Herbicide - spraying the individual weed plant with just enough herbicide to kill it. While there are risks (particularly unknown risks) with any herbicide, this approach enables choosing the least-harmful-known herbicide, as opposed to a chemical known to harm some kinds plants more than others.

- Mechanical Disruption - destroying the weed mechanically or disrupting the root systems so they can't survive.

- Burning - with a propane torch or similar.

However, for any specific mechanism to be effective it must be able to specifically target the weeds. This can be done either by dead reckoning or identification of weeds.

Grid-based dead reckoning is the mechanism employed by several system including Goat Industries' Weedinator. If you know the location of every plant in your crop (even if it is just the knowledge of them being in a grid with known separation and starting point), then disrupting everything in between the rows and columns (with a big egg-beater) will kill the weeds. There are also larger tractor-pulled machines which do similar things on a larger scale.

Individual identification can take at least two approaches.

- Knowing the location of every plant in the crop, and therefore assuming that any other plants are weeds. When the crop is planted, the location of every seed, or every seedling can be recorded. The current size of those plants can be estimated or measured (assuming they all grow at a similar rate). Any plant (pretty much anything non-dirt coloured) outside those boundaries can assumed to be plants. This involves an accurate navigation system, like DGPS down to a few centimetres.

- If the crop is a full cover crop (such as wheat, pasture etc), then the weed plants can be individually identified by picture. If you get lucky, and the weeds are a very different colour to the crop, then a camera system would work easily and well. For instance, even a system which would detect and target yellow flowers (St Johns Wort, Cape-weed etc) could be highly effective.

- Even if the differences in colour were not obvious to the human eye, the weeds may have very different reflective properties in the IR and UV spectrums. Most popular computer cameras have an IR filter (to remove the IR frequencies) which can be removed or replaced with an IR-only filter to see new frequencies. In particular Serrated Tussock is hard to differentiate from other weeds (such as native tussocks) even by humans - but do they look more different with other frequencies?

Some people might object to the notion of getting a robot to spray herbicide at all, based on an argument "we should work toward a solution which does away with potentially harmful chemicals altogether". This is admirable in intent, but not necessarily a realistic short or even medium-term goal.

Spot-spraying a general herbicide (such as Glyphosate) simply means less chemical sprayed around the place than blanketing a field with a specific herbicide. Glyphosate use is controversial, but the rational arguments against it are actually against its excessive use (not because of the excessive harmfulness of the chemical itself). Granted, there is no such thing as a good herbicide, but some are worse than others, and using less of any herbicide is a good thing - which is precisely what we are trying to achieve here.

Other mechanisms ..

A Google search reveals several interesting alternatives to spraying herbicide ..

Microwaving ..

Blasting the weeds briefly with microwaves to kill it (this seems a little high energy for a battery-powered rover).

Blasting the weeds briefly with microwaves to kill it (this seems a little high energy for a battery-powered rover).

See Video on how to cannibalise microwave ovens to produce microwaves.

Flame

Video of gas weeding torch.This looks good, but a robot with a flame-thrower is just a bit scary - especially in an area with a fire ban in place 6 months of the year.

The future

Develop a 'squirt' to aim a nozzle at a weed and spray it with a small (very carefully controlled) burst of herbicide (anyone with any experience with this is invited to write to me).

Leave a comment

Think I might have solved your problem? Ninety-nine problems, but your robot ain't one? Say so ..